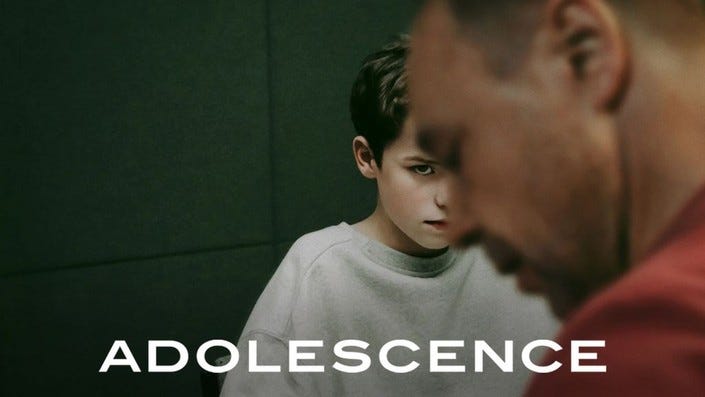

Every so often, a piece of culture reaches into you and sears your soul like a glowing cattle-brand. So it is with Netflix’s massive hit Adolescence. The fictional story of thirteen-year-old Jamie Miller, a charming but deeply troubled British boy, must be seen to be felt. As a father of a great boy, I can only say that Adolescence hit me so hard that it destabilized me. (It is a mature show and has some rough content; it is not for young viewers.)

The basic plot is simple (spoilers to follow). Jamie is accused of killing a young woman from his class named Katie. Over four episodes, the show probes this event, doing so in the famed “tracking shot” method that does not cut back and forth in typically edited fashion, but centers in continuous and unbroken on-screen action. The method is mesmeric. It is also, I suspect, a crucial part of the message.

Instead of looking away from this horrific tragedy, instead of relieving the tension (even briefly), cocreators Stephen Graham and Jack Thorne impel us to pay attention to it. For too long, we in the West have looked away from our boy crisis. We have not paid attention; we have not tracked what our sons are doing; we have not drawn near to them in order to guide and help them.

No longer, Graham and Thorne effectively say to us. Let us take stock of what we have done. Do not look away. Personally, I am glad for this theme. My 2023 book The War on Men represents my own personal attempt to ring the bell in the town square over the state of men today. For years now, the West has fed boys a poison diet, telling them they are “toxic.”

Alongside this vicious little judgment has come a wave of slogans: “Smash the patriarchy,” “the future is female,” and so on. Not for nothing did the University of Regina set up a “confession booth” to bid young men come and confess the innate wickedness of their biology.

Sensing they do not fit in to a woke and feminist culture, men have responded. As I cover in The War on Men, these responses are rarely positive or productive. Acting out of a sinful nature, some men disappear, dropping out of school. Some men turn to alcohol and drugs, lacking work. Some men go violent, attacking their spouse or local school. Some men kill themselves; the suicide rates among straight white adult middle-aged men are the highest of any group. The point is plain: we have told boys and men they are toxic, and they are taking the hint.

Adolescence does not cover all these matters. But the show’s unblinking study of Jamie’s downfall—when he was 13, barely old enough to stay up past 11 on the weekend—reveals (as I read it) that our boys have been failed at every level of society. His parents are disengaged from their son; the local school is a seething cauldron of barely-contained adolescent drama and its teachers have basically lost control of their classes; videos have taken the place of personal education; the court-appointed assessor of Jamie probes his psyche but offers him none of the affirmation he desperately seeks.

In Adolescence, we see that the kids are not okay—rather, the kids are on their own. Or, more to the point, they’re personally isolated but virtually surrounded. This is the modern social-media paradigm in a nutshell: alone but hounded. Along these lines, director Philip Barantini smashes the idea of a socially harmless Internet experience for children. Whatever the Internet used to be in 1995, when we first used it to send cheery emails and look up sunny vacation spots, it’s not that anymore.

This is laid bare in a spellbinding scene in episode 2. The teenage son of D. I. Bascombe, the officer leading the case against Jamie, enlightens his father as to the true dynamics of social media communication. The teenager clarifies that in the intricate codes of Instagram emojis, Katie was not flirting with Jamie (as the officer thought). The color of the heart emoji she left on Jamie’s account signals that she sees him as an “incel” (involuntary celibate), and thus demeaned him publicly.

In this way, the show exposes the evil online alchemy that seduces children today: 1) a girl (Katie) foolishly sends naked pictures of herself to a boy; 2) that boy passes them on to many others; 3) soon dozens of kids know of this; 4) they collectively evaluate and publicly mock Katie; 5) Jamie enters this sordid scene by asking Katie on a date in a genuinely kind action; 6) Katie reacts to this by rejecting Jamie and publicly treating him as an incel; 7) Jamie confronts her and murders her.

This is a complex situation to sort out, and the adults in Adolescence struggle to do so. Jamie’s parents fail to see that, though he seemed okay, he was in crisis. He is short, picked on, and thinks himself “ugly.” When he was cruelly scorned by Katie, her dismissal of him activated his unruly rage. Here is the sordid equation: relational cruelty spawns shamed powerlessness which leads to masculine violence.

As in Adolescence, so in the real world. Even before Jamie kills Katie, he turned in the closed-off privacy of his bedroom to the “manosphere.” There, he listened to one viral video after another, absorbing the anti-woman rants of Andrew Tate. He found in Tate, we can infer, a figure who Jamie felt could empower him to become the powerful man he is not.

This in, in actuality, a key part of Tate’s appeal. Though Tate is often dismissed with a hand-wave, he has won a major audience among young men because he firstly grasps their innate frustrations and secondly gives them a pathway to power. None of this is positive or good; as I’ve said before, Tate sells a cure as bad as the disease. But we cannot miss that Tate has cunningly figured out how to appeal to young men who feel shamed and disempowered in a culture that reads them as “toxic.”

With its targeting of young men, woke feminism has directly created the market for Tate. Disavowing angry young men, radical gender ideologues have ironically—and tragically—enabled the rise of this very group. As we see in Jamie’s case, he has no one who is drawing close to him to teach him a right understanding of strength. His father, Jamie haltingly shares in episode 3, signed him up for sports, but when Jamie struggled on the soccer field, his father reacted in embarrassment.

Eddie did not help Jamie process his son’s inadequacies. He effectively left Jamie to deal with his failure by himself. Reading into things a bit, Jamie was left with no outlet for his innate aggression and desire to achieve. After all, boys—and men—crave respect won by performance before their peers. They want to prove themselves; they want to level up; they want to be strong, and stand among the company of the courageous.

Think about what little boys do when around strong adult men. You might be at the park, minding your own business, when a plucky five-year-old approaches you. He tries to show off; he executes several daring stunts; he looks over to make sure you’re watching. This is all due to the wiring of boys. Boys want to be strong; they want to prove themselves, as this is actually a crucial part of their journey to manhood.

In our culture, these kind of instincts are seen as harmful. The behavior I’ve just described is labeled as part of “toxic masculinity.” But though these proclivities must be redeemed by the gospel and handled with wisdom by a wise and loving father, they are not inherently evil. Boys actually need to be called up. Not for nothing did dying David say to his son Solomon, “Be strong, and show yourself a man,” a demonstration anchored in the holiness of God (1 Kings 2:1-4).

This is extremely important in raising boys to men. In transforming sinful men into saints, Christ does not geld men. He does not convert them to gender-neutral beings, asking them to disown all traces of masculinity. No, in saving men, Christ calls men to holistic spiritual strength (Joshua 1; 1 Corinthians 16:13). But spiritual strength is not preening arrogance; it is humble and self-controlled, for it is grounded in God.

Strong men of God are not insecure like young Jamie is, then. Strong men of God do not need to enact violence to prove their manhood, as fragile men do. Truly strong men are men who know that they are inherently weak before God, and by God’s grace must be anchored in the finished work of Christ. Such men are cast in the mold of Jesus: gentle when needed, convictional when called upon, humble when challenged, bold when faced with danger, calm when tensions rise.

Woke feminism understands exactly none of this, to repeat the point. It wrongly conflates biblical strength with sinful power. It is this conflation that dooms woke feminism to its own demise, and endangers whole societies. If you remove the strong good men from a community, the strong evil men will not disappear. In the poignant language of American Sniper, you will instead have many wolves, and few sheepdogs.

Adolescence displays just such a context. There is indeed much evil coursing throughout, but from a Christian standpoint (my own), there is no one to stand it down. Viewed biblically, this is not merely because strong good men are missing—it is because Christ crucified and resurrected for hell-bound sinners is missing. Jamie lacks the gospel; his parents lack the gospel; his school lacks the gospel.

In Adolescence, redemption is everywhere needed, but nowhere found. The program is thus a powerful conversation-starter about our boy crisis, but it has no clear answers. Ultimately, Adolescence breaks your heart. In the last episode, on the father’s disastrous birthday 13 months after Jamie’s arrest, Jamie calls his dad and tells him that he is going to plead guilty to Katie’s murder. The family tries to live normally, but it is clear in episode 4 that everyone—father, mother, sister—hangs by a thread.

This comes to coherence in the show’s last scene. Jamie’s father, Eddie, does what he has not been able to do for a long time: he goes into Jamie’s bedroom. The last time we saw it, Jamie was in it when the police broke in and arrested him. The bedroom, once home to a lively teenage boy, is still and empty. The boyish wallpaper, and the teddy bear resting on the pillow, remind us of just how young Jamie is. So it is that our hearts break all over again.

Eddie gently takes the teddy bear, and sobs. “I’m sorry, son,” he weeps. “I failed you.” He has come full circle. In the show’s opening scene, he could not believe the charges against his son. As Adolescence wore on, he resisted accountability for his role in this tragedy, his anger exploding in the fourth and final episode. But now, he is humbled and quieted. He knows that, whatever else broke down, he did not pay sufficient attention to Jamie. In doing so, he lost his boy—forever.

This scene is not just an effective conclusion to a spellbinding piece of entertainment. As I interpret it, this scene is a call to accountability. For too long, we have ignored our sons. We have not heard them. We have not guided them out of rage and into peace. We have not lovingly but firmly disciplined them. In a single word, we have not loved them, for love asks all of these actions of fathers and mothers.

As I am at pains to say, our boy crisis is not just a sociological or cultural problem. Ultimately, this is a spiritual quagmire. We can take steps to repair our society (and we should do so). But let us not be confused. It is only God who can heal our boys, the very same boys who girls need for loving protection, provision, and leadership.

The need to engage boys with grace and truth is not new. It is ancient. In Malachi 4:5–6, a passage written thousands of years ago, we read this:

Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and awesome day of the LORD comes. And he will turn the hearts of fathers to their children and the hearts of children to their fathers, lest I come and strike the land with a decree of utter destruction.

The key to helping our boys is reawakening fathers. I do not mean this to the exclusion of mothers, for mothers are God-given and essential to the well-being of boys (and girls). But the center of the solution to our boy crisis is fathers. We do not just need nice fathers, though. We need men who know God through his gospel, and lead the next generation to do the same.

May it be so. May God, as in ancient days, turn the hearts of fathers to their children. And then, as men stir from their long slumber, may He turn the hearts of the children to their fathers. Do not be mistaken: at present, we are in crisis now. Our boys are in a dangerous place. But God, we cannot forget, is in the business of redeeming what seems irrecoverable, and reversing what seems hopelessly lost.

Thank you for this essay. I’ve been reading so much negative about this series and all of it from a racial perspective, “this isn’t happening by white boys, rather by immigrants.” I haven’t wanted to watch it and am not sure I’m ready to now but I can say I will read your book. I am a 72 year old former educator and 40 years ago I told my husband we could open a home with the fatherless young men/ boy students I knew who were looking for direction in their lives. I pray we made a difference in some. Thank you again for speaking of the need for Godly men to raise Godly boys into men.

Owen, I'm curious, have you addressed the fact elsewhere that this is a false narrative based on the murder of Elianne Andam by Hassan Sentamu? Truth matters.