Was Jesus nailed to the cross? Countless Christians think so, and innumerable hymns celebrate the nail-induced suffering of Christ on the cross in our place.

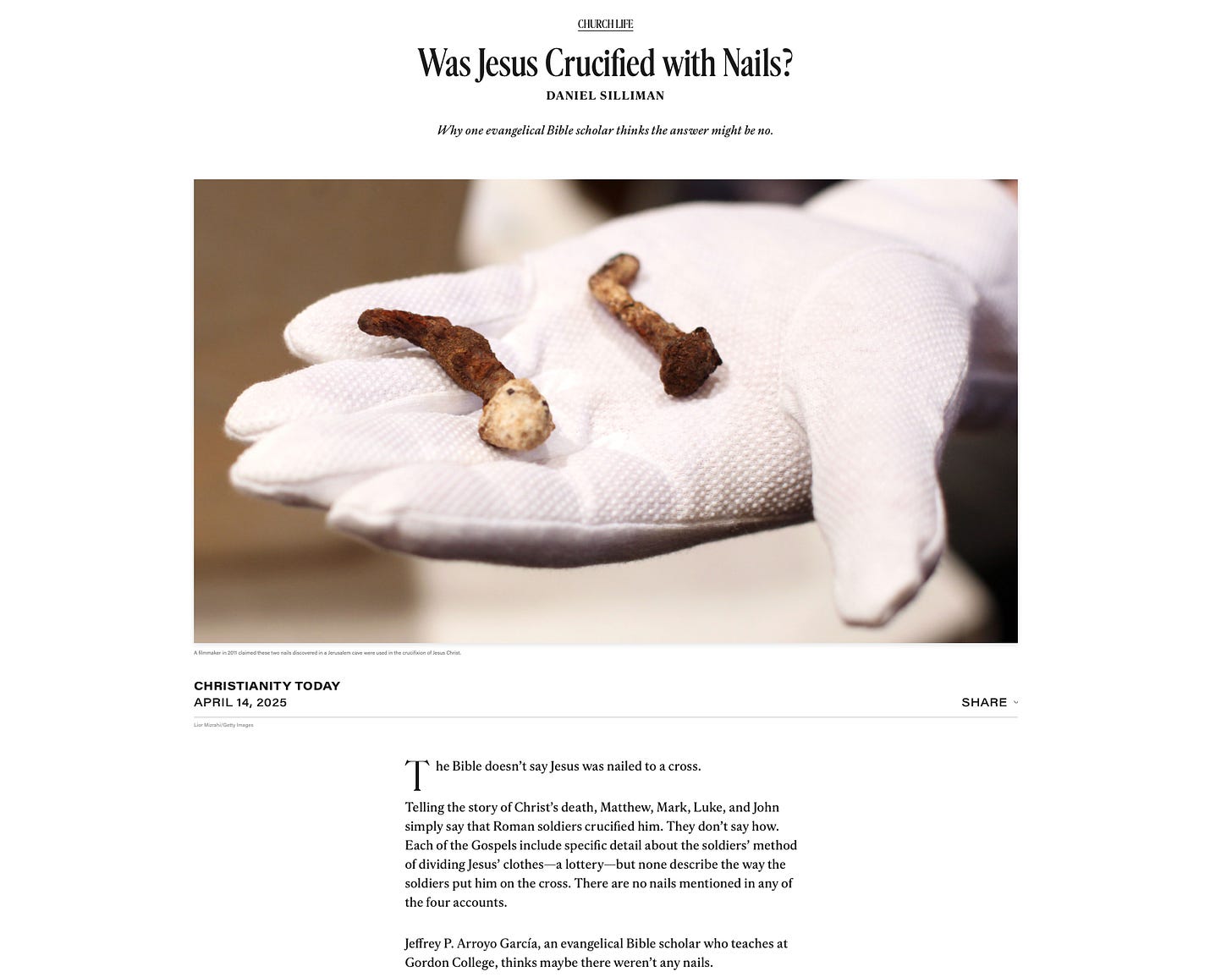

A new essay from Christianity Today, however, casts doubt on this detail of the atonement. In “Was Jesus Crucified with Nails?,” journalist Daniel Silliman covers the provocative case made by Gordon College professor Jeffrey P. Arroyo García in an article entitled “Nails or Knots—How Was Jesus Crucified?” for Biblical Archaeology Review. The essential argument made in the journal article is summed up in this passage of Silliman’s CT piece, referencing John 20:25 (more on this text to come):

Maybe that’s proof that Christ was crucified with nails, García said. But he isn’t completely convinced. Jesus doesn’t explicitly say “nails,” and the Bible does not say Thomas touches Christ’s hands or his feet. Many scholars think John was written later—perhaps after crucifixion with nails had become more common, García said.

Silliman and García have caused quite a stir with this thesis. The X post containing the Christianity Today article has over 2.2 million views and 3.4 thousand replies. This was no small stone to throw into the pond just before Good Friday and Easter. Because of the radical nature of this view, I noted a few posts on social media that wondered aloud, “Is this a Babylon Bee article?” (No, today, the Bee is generally more theologically conservative than Christianity Today—you can’t make this stuff up.)

The claims made by Silliman and García deserve a longer response. Here are four essential realities to consider about the nail-bearing cross of Christ.

First, the Bible clearly indicates that Jesus was nailed to the cross. This was prophesied in Psalm 22:16, which reads: “For dogs encompass me; a company of evildoers encircles me; they have pierced my hands and feet,” an unmistakable foretelling of the nail-involved crucifixion of the Messiah, a glorious subject I’ve written about in this 2024 resource.

This prophecy was clearly fulfilled in the New Testament. (We recall that the Scripture is one book written, ultimately, by one divine author, and it holds together in perfect harmony.) In Luke 24:36–43, Jesus appears to his disciples, who clearly have “doubts” about whether Christ is truly risen (38).

In response, Jesus says the following: “See my hands and my feet, that it is I myself. Touch me, and see. For a spirit does not have flesh and bones as you see that I have.” Following this, “he showed them his hands and his feet.” It makes little sense to conclude that Jesus is at this point showing his doubting disciples rope burn on his arms. It makes much more sense to reason that Jesus was giving them concrete proof that he was “pierced” in fulfillment of Psalm 22:16.

The second New Testament passage dealing with “nails” also—notably—deals with doubt. Thomas famously distrusts the resurrection of Jesus, and makes clear that he cannot believe unless he sees the disfigurement caused by nails with his own two eyes: “So the other disciples told him, “We have seen the Lord.” But he said to them, “Unless I see in his hands the mark of the nails, and place my finger into the mark of the nails, and place my hand into his side, I will never believe” (John 20:24-25).

The claim made by García (and Silliman) goes against the direct testimony of the apostles. Thomas knows what happened to Jesus at the cross; he knows that the πλευρὰν (“side”) of Jesus was pierced, just as he knows that ἥλων (“nails”) were driven into Jesus’ hands. There is a factual correlation here; Thomas cannot believe unless he sees the physical scars carved into Jesus’ body by Roman soldiers.

Jesus comes to Thomas and the disciples eight days later. When he comes, here is how he engages Thomas:

Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here, and see my hands; and put out your hand, and place it in my side. Do not disbelieve, but believe.” Thomas answered him, “My Lord and my God!” Jesus said to him, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed” (John 20:27-29).

Thomas, we should state, is not an idiot. Thomas is not worse than the rest of us doubt-prone disciples. To the contrary, Thomas is just like us. Yet note what Jesus does for Thomas: he ministers truth to him in love. He leads Thomas out of doubt. He does so not by preaching an angry hourlong sermon at him, but by directing Thomas to not only see his disfigured body, but to feel it. “Put your finger here,” Jesus commands, “and see my hands”; not only this, but “put out your hand” and then “place it in my side.”

The lesson is plain as day: just as Jesus’ “side” was gored by a spear, so Jesus’ hands were pierced (28). Thomas not only gets to take a look at this catalogue of suffering, this theology written into Christ’s frame. He gets to touch the bruised, broken, and now perfectly healed body of Christ. For the rest of his life, when Satanic doubts creep back into his mind, he can recall not only the sight of flesh torn by Roman nails, but the feel of it. (How’s that for an apologetic case?)

Total all this up, and we’re able to revisit the question raised by Christianity Today. Was Jesus nailed to the cross? Yes, he definitely was. The Romans may have crucified people in different ways, sure. I don’t doubt that that may well have happened; the Romans crucified many, many people, to be sure. But in the case of Jesus, their methods were clear as crystal: they pierced his hands and feet. In spite, they fulfilled Psalm 22. They tortured the Lord of glory, they split his flesh apart, and they did so without any awareness at all that they were ensuring our eternal salvation in doing so.

Second, García encourages us to doubt the biblical text. Earlier, I quoted the central claims made by the professor. We’ve seen unmistakable refutation of García’s claim that the Bible is not explicit about the piercing of Christ. This claim is very troubling, but so is a second one: García’s suggestion that “John was written later—perhaps after crucifixion with nails had become more common,” as Silliman reports.

This argument is slipped in toward the end of the Christianity Today article, but in truth, it’s about as subtle as a dynamite blast in your neighbor’s backyard. First, García works against the text, casting doubt on the actual words used by John. Second, García zooms out and questions the provenance of the entire passage, musing aloud that the passage in John 20 may well be apocryphal.

According to this professor, the Scripture is not trustworthy, in the end. It may be reporting what really happened with regard to the piercing of Christ, but it also may not be. So the academy tells us. “Many scholars” think that the Gospel of John has later additions, after all. The takeaway is plain: the biblical text is not straightforwardly factual. The consensus of “many scholars,” however, is.

I don’t want to be indelicate, but I cannot fail to tender an observation here. Liberalizing scholars are not actually against taking things on faith. They are not against trust. It is simply that they want us to trust them and not the Word of God. In their hands, the Bible is not objectively trustworthy. The scholarly consensus—left here in complete obscurity, we note—is objectively trustworthy.

So the point is this: everyone is equally exercising trust. Everyone on all sides—the conservative church and those who question its unscholarly and unlearned faith—is walking by faith. The question is simply this: who do you place your faith in? Who do you trust? Do you trust the Gospel of John? Or do you trust the “many scholars” Silliman cites, the company to which García belongs?

Third, García makes this argument by pitting Scripture against textual “backgrounds.” García and Silliman go into lots of detail about the logistics of Roman crucifixion. As a student of Scripture and history, I found this material engrossing. I’d love to learn more about crucifixion practice; after all, as a Western man, I think about the Roman Empire multiple times per week.

Textual background need not be pitted against the Word of God. We believers are not scared of deep study and comprehensive learning. Scholars have helped us on many counts, and we want seminarians to read widely, study intensely, and think critically. However, we always do so from a posture of reverence for the Bible itself. The Bible is central to our walk with God; intellectual Christians never stand above the Bible, never judge the Bible, and are not on par with the Bible. Nothing is, in fact.

For this reason, we must be careful with textual background material. It must always have second place; the background, we could say, must stay in the background. The biblical text itself is foremost; the Word of God alone in all the documents and research inquiries of our world is God-breathed, perfect, inerrant, and absolutely trustworthy (2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Peter 1:3).

So yes, “there is a world lying behind the text” as García notes. However, that world does not contradict the Bible. It may help us understand the Bible in places, but as a friend pointed out to me, the clear (Scripture) must interpret the less clear (ancient culture). The Bible is perspicuous, while the background of the first century must be worked out with great care. History does not determine Scripture; history is a witness to Scripture, and a welcome one, but the Word of God is the focus of our faith.

Silliman’s glowing profile of García includes the nugget that the professor nudges his students to “question tradition and what they think they know about Christ’s death and check it against Scripture.” This is not unsound as a formulation. “Tradition” can be many things, after all. But the glaring problem with García’s claims is that he is not taking his own medicine. Instead of questioning tradition and trusting Scripture, he is encouraging his students (and the rest of us) to question Scripture and check it against tradition.

Fourth, García separates trusting faith from biblical facticity. Silliman writes that at the conclusion of his article:

And the point of the gospel passage, the Gordon professor points out, is that followers of the resurrected Christ shouldn’t actually need nail holes to affirm their faith.

“Blessed are those who have not seen,” Jesus says, “and yet have believed” (v. 29).

This sounds pious and good. While I don’t know García’s heart, I do know this: this division of trusting faith and biblical facticity is unsound. It is not the move that Luke makes, for example. Luke writes to Theophilus so that his reader may have ἀσφάλειαν (“certainty”) about the life and ministry and work of Christ (Luke 1:4). His Gospel is shaped history, absolutely, but it is factual history that can bear the weight of total commitment—heart, mind, and soul—to Christ.

This principle is extremely important. The faith of Theophilus cannot rest on much truth and a little fiction, as Luke sees it. In accord with the other authors of the Bible, the faith of Theophilus must rest on “an orderly account” and a true “narrative” (Luke 1:3). If this is not so, Theophilus—like false disciples of many kinds—will be trusting what later Scripture calls “myths” and “cunning fables” (1 Timothy 1:4; 2 Peter 1:16).

We cannot underplay this point. The difference between following a “myth” and a true “narrative” is the difference between false faith and true faith. The Bible is not, then, a little dose of myth mixed with a whole lot of historical truth. No, the Bible is true in all it affirms. There are different genres of Scripture that require careful interpretive practice, sure. But all the historical material of the Bible is fact. It is all fact and no fiction.

You could sum up the principle I’m sketching this way: historicity drives facticity, facticity determines truthfulness, and truthfulness undergirds saving faith. Take away historical truthfulness, and the Bible is no longer the Bible. The stakes are very high here indeed. Liberalizing voices have tried to separate Christianity from facticity for generations now. For centuries, scholars have made detailed cases for why one historical element of the Bible or another is mythological. For centuries, the believing church has resisted these trends.

We do so not in angry truculence, reflexive anti-intellectualism, or vengeful disagreement. No, we resist the “many scholars” who encourage us to doubt plain biblical teaching in love, in faith, and in hope. We want to glorify God as those justified by faith (and not by doubt). Further, we have a faith to hand on to our children and our grandchildren after that.

In seeking this end, we know that we are not at all better than Thomas, Jeffrey P. Arroyo García, Daniel Silliman, and all else who doubt God. We all doubt God at some level. We all sin in this way. The biblical authors did not include the passages from Luke 23 and John 20 to shame the disciples and mock them. Under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, Luke and John wrote this material to reveal how breathtakingly easy it is for all God’s people—and for the sinful human heart we all have—to doubt God.

Conclusion

Faith is not natural, we see; doubt is. Faith is a miracle. To oppose it, Satan will continue to send winds of doubt and despair and confusion. What did Paul warn us about? In Ephesians 4:18, he cautioned that the Gentiles “are darkened in their understanding, alienated from the life of God because of the ignorance that is in them, due to their hardness of heart.”

How we must hear this warning afresh in our time. Until the end of the age, Satan will work to destabilize our faith. He will continue to attack biblical revelation, biblical authority, and biblically-grounded faith. Knowing this, let us pray for García, Silliman, the leaders of Christianity Today, and our own straying minds. Let us ask God to give them—and us—fresh repentance, fresh faith, and fresh love.

And let us remember as well that we are not deprived disciples. We are not in a worse place than Thomas. According to the apostle Peter, the Word of God is no lesser witness to the greatness of Christ and the majesty of God. It is “a more sure Word” (2 Peter 1:19). It is the very testimony of heaven, the unbreakable oath of God, the one perfectly truthful record of the wonder-working life and ministry of Christ Jesus.

Let us trust this Word, brothers and sisters. There will be rewards for doing so, we remember. What did Jesus say so long ago? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed. Until the end, let us believe, and when we fail to do so, let us confess our sin, and return to the God who forgives the doubter and strengthens the weak—namely, us.

For some time I have thought that “Christianity Today” is well named. And that is not intended to be a compliment.

Man, isn’t this so common nowadays?

“The takeaway is plain: the biblical text is not straightforwardly factual. The consensus of “many scholars,” however, is.”

It is the not so subtle shift to humanism. Replacing the divine reality of Christ and the word of God with the “factual certainty” of collective scientists/scholars/professionals.